You should spend about 20

minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

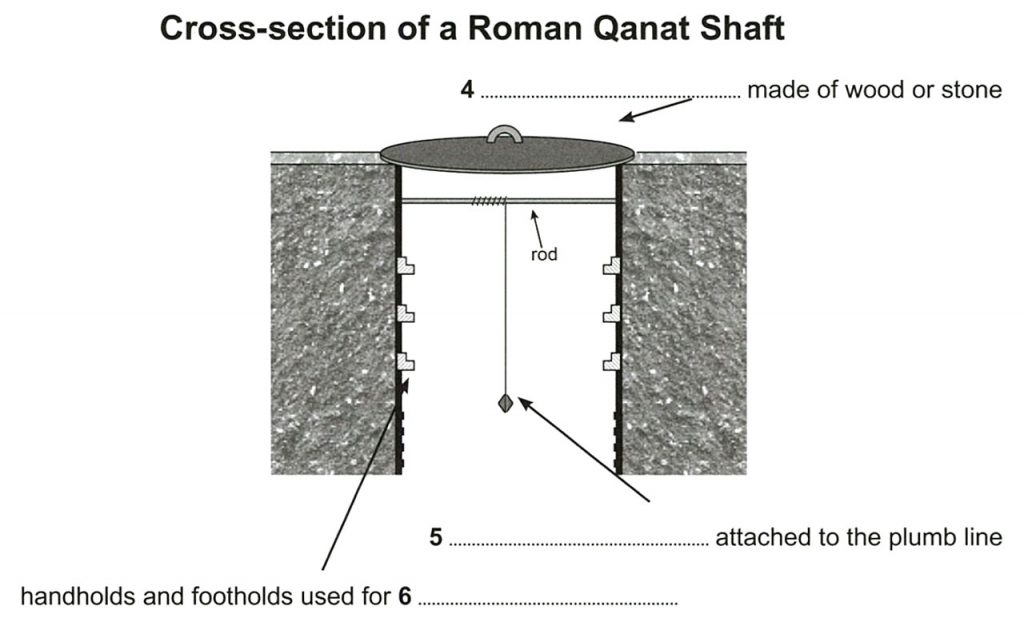

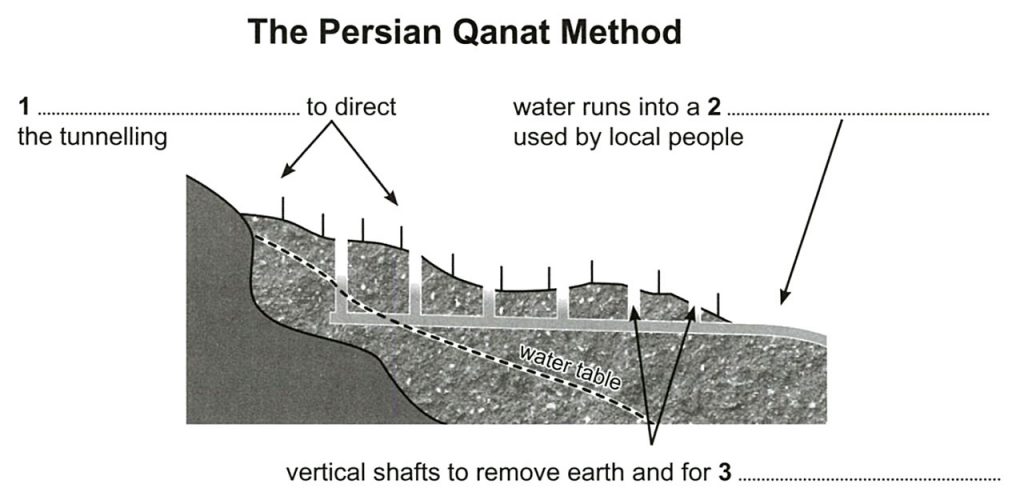

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet.

Do the following statements

agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 7-10 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE

if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE

if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no

information on this

7 The

counter-excavation method completely replaced the qanat method in the 6th

century BCE.

8 Only experienced builders were employed to construct

a tunnel using the counter-excavation method.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 11-13 on your answer sheet.

11 What type of

mineral were the Dolaucothi mines in Wales built to extract?

12 In addition to the patron, whose name might be carved

onto a tunnel?

13 What part of Seleuceia Pieria was the Çevlik tunnel

built to protect?

READING

PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20

minutes on Questions 14-26 which are based on

Reading Passage 2 below.

Changes in

reading habits

What are the implications of the way we read today?

Look around on your next plane

trip. The iPad is the new pacifier for babies and toddlers. Younger school-aged

children read stories on smartphones; older kids don’t read at all, but hunch

over video games. Parents and other passengers read on tablets or skim a

flotilla of email and news feeds. Unbeknown to most of us, an invisible,

game-changing transformation links everyone in this picture: the neuronal

circuit that underlies the brain’s ability to read is subtly, rapidly changing

and this has implications for everyone from the pre-reading toddler to the

expert adult.

As work in neurosciences

indicates, the acquisition of literacy necessitated a new circuit in our

species’ brain more than 6,000 years ago. That circuit evolved from a very

simple mechanism for decoding basic information, like the number of goats in

one’s herd, to the present, highly elaborated reading brain. My research

depicts how the present reading brain enables the development of some of our

most important intellectual and affective processes: internalized knowledge,

analogical reasoning, and inference; perspective-taking and empathy; critical

analysis and the generation of insight. Research surfacing in many parts of the

world now cautions that each of these essential ‘deep reading’ processes may be

under threat as we move into digital-based modes of reading.

This is not a simple, binary

issue of print versus digital reading and technological innovations. As MIT

scholar Sherry Turkle has written, we do not err as a society when we innovate

but when we ignore what we disrupt or diminish while innovating. In this hinge

moment between print and digital cultures, society needs to confront what is

diminishing in the expert reading circuit, what our children and older students

are not developing, and what we can do about it.

We know from research that the

reading circuit is not given to human beings through a genetic blueprint like

vision or language; it needs an environment to develop. Further, it will adapt

to that environment’s requirements – from different writing systems to the

characteristics of whatever medium is used. If the dominant medium advantages

processes that are fast, multi-task oriented and well-suited for large volumes

of information, like the current digital medium, so will the reading circuit.

As UCLA psychologist Patricia Greenfield writes, the result is that less

attention and time will be allocated to slower, time-demanding deep reading

processes.

Increasing reports from

educators and from researchers in psychology and the humanities bear this out.

English literature scholar and teacher Mark Edmundson describes how many

college students actively avoid the classic literature of the 19th and 20th

centuries in favour of something simpler as they no longer have the patience to

read longer, denser, more difficult texts. We should be less concerned with

students’ ‘cognitive impatience’, however, than by what may underlie it: the

potential inability of large numbers of students to read with a level of

critical analysis sufficient to comprehend the complexity of thought and

argument found in more demanding texts.

Multiple studies show that

digital screen use may be causing a variety of troubling downstream effects on

reading comprehension in older high school and college students. In Stavanger,

Norway, psychologist Anne Mangen and colleagues studied how high school

students comprehend the same material in different mediums. Mangen’s group

asked subjects questions about a short story whose plot had universal student

appeal; half of the students read the story on a tablet, the other half in

paperback. Results indicated that students who read on print were superior in

their comprehension to screen-reading peers, particularly in their ability to

sequence detail and reconstruct the plot in chronological order.

Ziming Liu from San Jose State

University has conducted a series of studies which indicate that the ‘new norm’

in reading is skimming, involving word-spotting and browsing through the text.

Many readers now use a pattern when reading in which they sample the first line

and then word-spot through the rest of the text. When the reading brain skims

like this, it reduces time allocated to deep reading processes. In other words,

we don’t have time to grasp complexity, to understand another’s feelings, to

perceive beauty, and to create thoughts of the reader’s own.

The possibility that critical

analysis, empathy and other deep reading processes could become the unintended

‘collateral damage’ of our digital culture is not a straightforward binary issue

about print versus digital reading. It is about how we all have begun to read o

various mediums and how that changes not only what we read, but also the

purposes for which we read. Nor is it only about the young. The subtle atrophy

of critical analysis and empathy affects us all equally. It affects our ability

to navigate a constant bombardment of information. It incentivizes a retreat to

the most familiar stores of unchecked information, which require and receive no

analysis, leaving us susceptible to false information and irrational ideas.

There’s an old rule in

neuroscience that does not alter with age: use it or lose it. It is a very

hopeful principle when applied to critical thought in the reading brain because

it implies choice. The story of the changing reading brain is hardly finished.

We possess both the science and the technology to identify and redress the

changes in how we read before they become entrenched. If we work to understand

exactly what we will lose, alongside the extraordinary new capacities that the

digital world has brought us, there is as much reason for excitement as caution.

Questions 14-17

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 14-17 on your answer sheet.

14 What is the

writer’s main point in the first paragraph?

A Our use of technology is having a hidden

effect on us.

B Technology can be used to help youngsters to

read.

C Travellers should be encouraged to use

technology on planes.

D Playing games is a more popular use of

technology than reading.

15 What main point

does Sherry Turkle make about innovation?

A Technological innovation has led to a

reduction in print reading.

B We should pay attention to what might be lost

when innovation occurs.

C We should encourage more young people to

become involved in innovation.

D There is a difference between developing

products and developing ideas.

16 What point is the

writer making in the fourth paragraph?

A Humans have an inborn ability to read

and write.

B Reading can be done using many different

mediums.

C Writing systems make unexpected demands

on the brain.

D Some brain circuits adjust to whatever

is required of them.

17 According to Mark

Edmundson, the attitude of college students

A has changed the way he teaches.

B has influenced what they select to read.

C does not worry him as much as it does

others.

D does not match the views of the general

public.

Questions 18-22

Complete the summary using the

list of words, A-H, below.

Write the correct letter, A-H, in boxes 18-22 on your answer

sheet.

Studies on

digital screen use

There have been many studies on

digital screen use, showing some 18 ………………… trends. Psychologist

Anne Mangen gave high-school students a short story to read, half using digital

and half using print mediums. Her team then used a question-and-answer

technique to find out how 19 ………………… each group’s

understanding of the plot was. The findings showed a clear pattern in the

responses, with those who read screens finding the order of information 20 ………………… to recall.

Studies by Ziming Liu show that

students are tending to read 21 ………………… words and phrases in a

text to save time. This approach, she says, gives the reader a superficial

understanding of the 22 ………………… content of material,

leaving no time for thought.

A fast B isolated C

emotional D worrying

E many F hard G

combined H thorough

Questions 23-26

Do the following statements

agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage 2?

In boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE

if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

FALSE

if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is

impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

23 The medium we use

to read can affect our choice of reading content.

24 Some age groups are more likely to lose their complex

reading skills than others.

25 False information has become more widespread in

today’s digital era.

26 We still have opportunities to rectify the problems

that technology is presenting.

READING

PASSAGE 3

You should spend about 20

minutes on Questions 27-40 which are based on

Reading Passage 3 below.

Attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence

A

Artificial intelligence (AI)

can already predict the future. Police forces are using it to map when and

where crime is likely to occur. Doctors can use it to predict when a patient is

most likely to have a heart attack or stroke. Researchers are even trying to

give AI imagination so it can plan for unexpected consequences.

Many decisions in our lives

require a good forecast, and AI is almost always better at forecasting than we

are. Yet for all these technological advances, we still seem to deeply lack

confidence in AI predictions. Recent cases show that people don’t like relying

on AI and prefer to trust human experts, even if these experts are wrong.

If we want AI to really benefit

people, we need to find a way to get people to trust it. To do that, we need to

understand why people are so reluctant to trust AI in the first place.

B

Take the case of Watson for

Oncology, one of technology giant IBM’s supercomputer programs. Their attempt

to promote this program to cancer doctors was a PR disaster. The AI promised to

deliver top-quality recommendations on the treatment of 12 cancers that

accounted for 80% of the world’s cases. But when doctors first interacted with

Watson, they found themselves in a rather difficult situation. On the one hand,

if Watson provided guidance about a treatment that coincided with their own

opinions, physicians did not see much point in Watson’s recommendations. The

supercomputer was simply telling them what they already knew, and these

recommendations did not change the actual treatment.

On the other hand, if Watson

generated a recommendation that contradicted the experts’ opinion, doctors

would typically conclude that Watson wasn’t competent. And the machine wouldn’t

be able to explain why its treatment was plausible because its machine-learning

algorithms were simply too complex to be fully understood by humans.

Consequently, this has caused even more suspicion and disbelief, leading many

doctors to ignore the seemingly outlandish AI recommendations and stick to

their own expertise.

C

This is just one example of

people’s lack of confidence in AI and their reluctance to accept what AI has to

offer. Trust in other people is often based on our understanding of how others

think and having experience of their reliability. This helps create a

psychological feeling of safety. AI, on the other hand, is still fairly new and

unfamiliar to most people. Even if it can be technically explained (and that’s

not always the case), AI’s decision-making process is usually too difficult for

most people to comprehend. And interacting with something we don’t understand

can cause anxiety and give us a sense that we’re losing control.

Many people are also simply not

familiar with many instances of AI actually working, because it often happens

in the background. Instead, they are acutely aware of instances where AI goes

wrong. Embarrassing AI failures receive a disproportionate amount of media

attention, emphasising the message that we cannot rely on technology. Machine

learning is not foolproof, in part because the humans who design it aren’t.

D

Feelings about AI run deep. In

a recent experiment, people from a range of backgrounds were given various

sci-fi films about AI to watch and then asked questions about automation in

everyday life. It was found that, regardless of whether the film they watched

depicted AI in a positive or negative light, simply watching a cinematic vision

of our technological future polarised the participants’ attitudes. Optimists

became more extreme in their enthusiasm for AI and sceptics became even more

guarded.

This suggests people use

relevant evidence about AI in a biased manner to support their existing

attitudes, a deep-rooted human tendency known as “confirmation bias”. As AI is

represented more and more in media and entertainment, it could lead to a

society split between those who benefit from AI and those who reject it. More

pertinently, refusing to accept the advantages offered by AI could place a

large group of people at a serious disadvantage.

E

Fortunately, we already have

some ideas about how to improve trust in AI. Simply having previous experience

with AI can significantly improve people’s opinions about the technology, as

was found in the study mentioned above. Evidence also suggests the more you use

other technologies such as the internet, the more you trust them.

Another solution may be to

reveal more about the algorithms which AI uses and the purposes they serve. Several

high-profile social media companies and online marketplaces already release

transparency reports about government requests and surveillance disclosures. A

similar practice for AI could help people have a better understanding of the

way algorithmic decisions are made.

F

Research suggests that allowing

people some control over AI decision-making could also improve trust and enable

AI to learn from human experience. For example, one study showed that when

people were allowed the freedom to slightly modify an algorithm, they felt more

satisfied with its decisions, more likely to believe it was superior and more

likely to use it in the future.

We don’t need to understand the

intricate inner workings of AI systems, but if people are given a degree of

responsibility for how they are implemented, they will be more willing to

accept AI into their lives.

Questions 27-32

Reading Passage 3 has six

sections, A-F.

Choose the correct heading for

each section from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number, i-viii, in boxes 27-32 on your answer

sheet.

List of Headings

i An increasing divergence

of attitudes towards AI

ii Reasons why we have more

faith in human judgement than in AI

iii The superiority of AI projections over

those made by humans

iv The process by which AI can help us make

good decisions

v The advantages of

involving users in AI processes

vi Widespread distrust of an AI innovation

vii Encouraging openness about how AI

functions

viii A surprisingly successful AI application

27 Section A

28 Section B

29 Section C

30 Section D

31 Section E

32 Section F

Question 33-35

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 33-35 on your answer sheet.

33 What is the writer

doing in Section A?

A providing a solution to a concern

B justifying an opinion about an issue

C highlighting the existence of a problem

D explaining the reasons for a phenomenon

34 According to

Section C, why might some people be reluctant to accept AI?

A They are afraid it will replace humans in

decision-making jobs.

B Its complexity makes them feel that they are at a

disadvantage.

C They would rather wait for the technology to be

tested over a period of time.

D Misunderstandings about how it works make it seem

more challenging than it is.

35 What does the

writer say about the media in Section C of the text?

A It leads the public to be mistrustful of AI.

B It devotes an excessive amount of attention to AI.

C Its reports of incidents involving AI are often

inaccurate.

D It gives the impression that AI failures are due to

designer error.

Questions 36-40

Do the following statements

agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet, write

YES

if the

statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO

if the

statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is

impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

36 Subjective

depictions of AI in sci-fi films make people change their opinions about

automation.

37 Portrayals of AI in media and entertainment are likely

to become more positive.

38 Rejection of the possibilities of AI may have a

negative effect on many people’s lives.

39 Familiarity with AI has very little impact on people’s

attitudes to the technology.

40 AI applications which users are able to modify are

more likely to gain consumer approval .

ANSWERS

Passage 1

1 posts

2 canal

3 ventilation

4 lid

5 weight

6 climbing

7 FALSE

8 NOT GIVEN

9 FALSE

10 TRUE

11 gold

12 (the) architect(‘s) (name)

13 (the) harbour / harbor

Passage 2

14 A

15 B

16 D

17 B

18 D

19 H

20 F

21 B

22 C

23 YES

24 NO

25 NOT GIVEN

26 YES

Passage 3

27 iii

28 vi

29 ii

30 i

31 vii

32 v

33 C

34 B

35 A

36 NO

37 NOT GIVEN

38 YES

39 NO

40 YES

No comments:

Post a Comment